|

During my four year art education condensed into three years, I was given the option of either entering fine art or commercial art program. I never wanted to be a starving artist, so I continuing studying illustration and graphic design, along with other creative disciplines. All related subjects were exciting as an art student. This prepared me for working in the commercial art field as a graphic designer and illustrator. It was very difficult finding a job initially, because it was mostly male dominated and I had no previous work experience in the advertising field. At one interview I was told that I would not be hired because I was a woman, and that they would not waste their time training me, because I would be married soon and have a family. That was the climate at that time. I was completely unaware how unfair this was. Well, guess what, I’m still here.

Eventually, I was hired and worked in this field for over 20 years in advertising nationally and internationally in graphic design and illustration. But, there were sacrifices in both health and well being because creativity was stunted. As a graphic designer, this meant understanding design, composition, typography, fonts, headings, body copy, and designing appealing spaces in between text so that the reader could easily navigate through the information. On the illustration front, I worked initially as an illustrator for a greeting card company, then as a food, and figurative illustrator and graphic designer for retail food chain. Followed by an advertising agency, creating brochures and illustrations for publication. Then an illustrator for a major retail chain, working as a layout artist in the fashion department. This involved drawing female fashion figures wearing specific garment as stipulated by buyers. These pages in turn were sent to photographers as a guide to shoot photographs of models that were printed in catalogues. Another job was to create illustrations depicting cottage country scenes including birds, muskoka chairs, lakes, flowers, trees, and more. This also involved all levels of production for silk screen printing. Lastly, I was hired as Art Director for a different company. I learned that this was not what I was cut out for, and eventually quit. Afterwards, I did a number of freelance editorial illustrations mostly for US magazines and international clients. When there was no longer a demand for this type of work, I then transitioned gradually into landscape paintings. This was the beginning of a long journey of transformation in myself, and my art. Commercially, the take away for me was that I developed refined skills in drawing and painting and a keen eye for colour, design and space relationship. Following all that I began to teach art at college and art organizations. At college, I was asked to teach computer graphics and digital illustration. Class sizes were approximately 35 students per class. I discovered that I enjoyed the interaction between students and myself. On occasion a student would work on a visual project that also inspired me. I also taught art groups and in art galleries plus art societies watercolour landscapes, figurative and portrait subject matter.

0 Comments

I was never a stellar student at school in my childhood. In fact, even before I began school in kindergarten at the age of 5, I felt as if I was going to enter a prison of sort.

It wasn’t until I began studying art at age 17 that I felt I found a sense of belonging, a home for learning that felt ‘right’. Teachers had high expectations from students and we had to work hard. I remember one time when we were given an assignment that I was quite excited about and spent approximately two weeks working on this artwork, putting in 12 hours days. When I handed in the assignment, I failed. I was so angry that I went home and using this anger, created new artwork which was done quick and simple. I handed this in to my art teacher and asked if I could replace the old with the new. The answer was yes. I received a 97 out of a 100 grade. I have never forgotten this lesson. I learned that I killed the artwork by overworking and overthinking. But when created from a place of energy, it then communicates more than a pretty picture. The foundation of training, skill and raw talent still needs to be there. My years of art education were wonderful even though they were not always easy, They also filled a void that formal education didn’t. With a total of seven years of formal.training including the many disciplines from industrial design, anatomy, metal work, sculpture, typography, art history, drawing and painting and more, laid an unshakable foundation. In the academic environment I found history boring and dates didn’t mean much to me. But when I studied art history a whole new world came to life which is still present today. When I transitioning to abstract painting later in life it wasn’t by choice. I was offered to teach a class in abstract painting. Moving away from representational and realistic depictions towards non-representational was a gradual shift and continues today because there is continuous growth visually and mentally.

Although I didn’t know at the time, this shift can be driven by various factors such as personal life experiences, exploration, experimentation, or to convey emotions and ideas that visually communicate and excite. What also contributed to this shift, was a video I watched of a German artist Gerhard Richter. When he transitioned from high realism portrait paintings into abstract painting, with the following comment “ my best work ever ” THIS I finally understood. It was an eye-opener. Creative satisfaction can come from any form of discipline. In my case it was abstract painting. But this transition wasn’t easy. And failure is a part of this process. It’s difficult to embrace failure, but it’s necessary. It’s about searching. Most of my paintings have layers upon layers upon layers underneath before the painting reveals itself. These steps involve so many parts of my mental focus that it feels like my mind is exploding. When unexpected surprises appear, there is joy, but there’s no guarantee that the end this result will be an acceptable painting if consistency is absent. The biggest struggle is surrendering control. It’s a constant struggle to abandon everything I had been taught and not knowing where I would end up. But it’s in my curious nature not to give up. As an art instructor, I learn from my students, and they in turn learn from my contribution based on my past working experience. Enthusiasm and a sense of curiosity in an art class environment can heighten a sense of joy and belonging. How to achieve the sense of well-being and its many benefits is to be involved in creating on a regular basis, and to take risks. Embracing a full range of emotional connections add to this growth. Visually, there are many levels of creative expression from minimal to maximum. A valuable reminder for me is my 30+ years of working experience in the advertising field as as illustrator and graphic designer was only the beginning. As a visual artist, Neuro creativity and Neuroaesthetics is now proving through scientific research what I have felt and suspected over the past number of years.

More to come, as I learn more. From Nautilus Magazine

The creative spark can flare up in anyone at any time. For the cognitive neuroscientist Evangelia Chrysikou, who grew up in Greece, creativity is almost a fundamental human instinct. We wouldn’t be where we are today as a species, spread across the globe, she says, if we couldn’t imagine what’s possible—and make it happen. For her, all creative acts fall along a spectrum of recombining what you know into something that didn’t previously exist. She offers a simple example of what you might do if you’re sitting on a chair in a room and someone attacks you. “You will very quickly rearrange your thinking about what the chair is, and use it as a shield, or use other items around you as a weapon,” she says. “What I have found fascinating is, clearly we can all do it, but what are these processes? There’s something in our brain that lets us take something that, everyday, you use as a pen, and immediately reorganize it into something that has other kinds of characteristics that can serve a different purpose,” like a tiny spear. In her lab at Drexel University, she probes brain activity with fMRI machines and transcranial electrical stimulation to understand what underpins our ability to think flexibly and solve problems. Creative acts rely on access to particular knowledge. In a new study, she assembled a group of 20 “eminent” creators, people with “exceptionally high creativity,” and matched them with a control group—people of the same age and educational and professional background—with lesser powers of creativity. (The researchers assessed subjects’ creativity based on responses to a “creative achievement questionnaire.”) She, Andrew Newberg of Thomas Jefferson University, Scott Barry Kaufman of Columbia University, and other colleagues, wanted to find out what in the brain might explain some of the differences in creative achievement between these groups. Among other things, the researchers monitored the blood-oxygenation levels of the participants’ brains while in a resting state—while they weren’t performing any task—to compare how different the functional connections are between certain areas of the brain for each group. Nautilus caught up with Chrysikou recently to discuss her findings. Are there any notable differences in the brains of “eminent” creative people compared to those who are merely successful and smart? Yes. So in this recent study, conducted at Thomas Jefferson University, we wanted to find out whether there’s something about how the different parts of the brain talk to each other under rest, where there is no particular task to be achieved. Is there something about the connectedness of the different regions of the brain within the eminent group that differs from the non-eminent group, and how are these related to the creative success of the participants? The key finding was that, for the eminent creators, there was a higher connectivity, both within each hemisphere, the right and left, but particularly across them—and especially in the two key networks that many studies have identified as important for creative thinking, the default mode network and the executive control network. Past research has shown that, during most of our day-to-day activities, these two networks are antagonistic. In creative tasks, they seem to be talking a little bit more with each other. In this particular study, our results mirror this finding. For the eminent creators, there was much more dialogue between these two networks relative to the non-eminent creators. When the participants were completing the alternative uses task—the traditional measure for creativity, where you show people an object and you ask them in a few seconds to verbally generate an alternative use for it—the brains of eminent creators were more efficient, meaning the recruitment of brain regions was much more focused compared to the non-eminent creators, whose recruitment of brain regions was more variable, widespread, and less organized. In other words, the brain areas that support creative functions were activated and engaged in eminent creators more often and more strongly and with more specificity. This was true across the eminent creator group, whether they were famous artists, writers, or lawyers, which I think is a really cool finding. How might you explain your findings in terms of what’s happening psychologically? Given what we know about the default mode network, which activates strongly when we remember the past and imagine the future, and the executive control network, which activates when we carry out our plans, our finding suggests that creative acts rely on access to particular knowledge. You have memories about the world around you, about how things work, how things operate. These memories are retrieved in certain ways, depending on the context of a particular goal you have to achieve. So the brains of highly creative people engage in this dialogue or filtering of the memory search process based on the context, the tasks that they have to accomplish, especially when they are creating something new. That memory search also helps you reinterpret the particular object. We need to do much more experimental work to be able to say, “Here is this particular kind of memory that was reorganized.” The level of resolution of the results we have is a little bit fuzzier than that. But it’s still a very interesting first step toward addressing that question of how you borrow from memory to create things that don’t exist. “The difference between abstract and representational painting is that once the action of painting in abstraction is experienced, nothing can stop that freedom.”

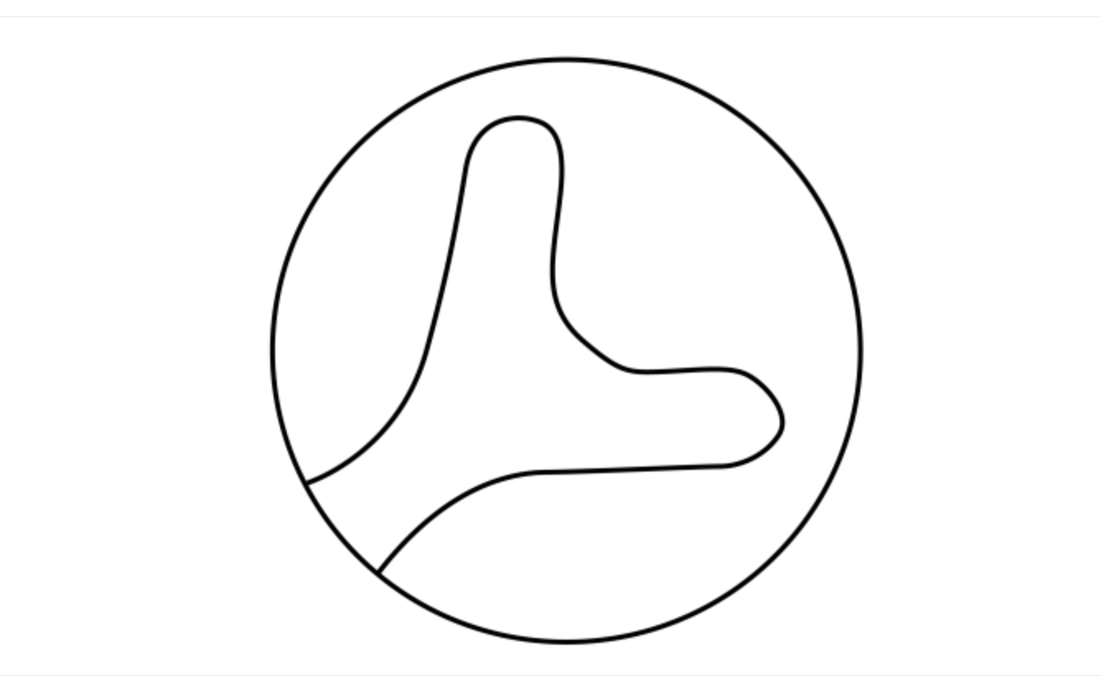

David Bowie on Art https://youtu.be/JRtZc_Nmo5w Shared quotes with Elizabeth Gilbert. You might think that new, innovative projects frustrate you. News flash: they frustrate everybody. Many talented, creative, and inventive people rage against their work, or even worse, stop doing their work because of the frustration that they encountered along the path of whatever it was they were trying to create. And they speak of this frustration as though it is this obstacle from outer space that is ruining everything,” But this discouragement comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of the relationship between frustration and creativity. “The frustration, the hard part, the obstacle, the insecurities, the difficulty, the ‘I don't know what to do with this thing now,’ that's the creative process. So stop trying to find a solution that will make creativity easy or painless. It doesn't exist, and if you're not sweating and suffering at some time, the results almost certainly won't qualify as creative. Don't try to go to war against it, that's such a waste of energy. Just converse with it and then move on. Creativity can seem like magic -; one day the muse sings or lightning strikes and you’re gifted with a fully formed idea that changes everything. Viewed this way, creativity appears to be the province of the lucky few, but both science and many artists insist creativity is much more everyday than that. Mostly it boils down to combining old ideas in different ways, or porting insights from one area of endeavor to another. Rather than springing into the world fully-formed, new invention is essentially the random mutation of old ideas. When those ideas prove useful, they expand to fill a new niche. The key to experiencing more breakthroughs is often to stop waiting for eureka moments to allow yourself to play and experiment more with ideas and concepts you’re already familiar with. Feature Artist: Brice Marden https://youtu.be/9ebExAsHZMg That’s not how the Brain Works. Lisa Feldman Barrett (@LFeldmanBarrett) is a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and the author of Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain. Learn more at LisaFeldmanBarrett.com. Forget scientific myths to better understand your brain and yourself. So why does the myth of a compartmentalized brain persist? One reason is that brain-scanning studies are expensive. As a compromise, typical studies include only enough scanning to show the strongest, most robust brain activity. These underpowered studies produce pretty pictures that appear to show little islands of activity in a calm-looking brain. But they miss plenty of other, less robust activity that may still be psychologically and biologically meaningful. In contrast, when studies are run with enough power, they show activity in the majority of the brain, Pretty much everything that your brain creates, from sights and sounds to memories and emotions, involves your whole brain. Every neuron communicates with thousands of others at the same time. In such a complex system, very little that you do or experience can be traced to a simple sum of parts. Brains don’t work by stimulus and response. All your neurons are firing at various rates all the time. What are they doing? Busily making predictions. In every moment, your brain uses all its available information (your memory, your situation, the state of your body) to take guesses about what will happen in the next moment. If a guess turns out to be correct, your brain has a head start: It’s already launching your body’s next actions and creating what you see, hear, and feel. If a guess is wrong, the brain can correct itself and hopefully learn to predict better next time. Or sometimes it doesn’t bother correcting the guess, and you might see or hear things that aren’t present or do something that you didn’t consciously intend. All of this prediction and correction happens in the blink of an eye, outside your awareness. If a predicting brain sounds like science fiction, here’s a quick demonstration. What is this picture? If you see only some curvy lines, then your brain is trying to make a good prediction and failing. It can’t match this picture to something similar in your past. (Scientists call this state “experiential blindness.”) Then come back and look at the picture again. Suddenly, your brain can make meaning of the picture. The description gave your brain new information, which conjured up similar experiences in your past, and your brain used those experiences to launch better predictions for what you should see. Your brain has transformed ambiguous, curvy lines into a meaningful perception. (You will probably never see this picture as meaningless again.)

You’re not a simple stimulus-response organism. The experiences you have today influence the actions that your brain automatically launches tomorrow. The myth is that there’s a clear dividing line between diseases of the body, such as cardiovascular disease, and diseases of the mind, such as depression. The idea that body and mind are separate was popularized by the philosopher René Descartes in the 17th century (known as Cartesian dualism) and it’s still around today, including in the practice of medicine. Neuroscientists have found, however, that the same brain networks responsible for controlling your body also are involved in creating your mind. A great example is the anterior cingulate cortex, mentioned earlier. Its neurons not only participate in all the psychological functions, but also they regulate your organs, hormones, and immune system to keep you alive and well. Every mental experience has physical causes, and physical changes in your body often have mental consequences, thanks to your predicting brain. In every moment, your brain makes meaning of the whirlwind of activity inside your body, just as it does with sense data from the outside world. When thinking about the relationship between mind and body, it’s tempting to indulge in the myth that the mind is solely in the brain and the body is separate. Under the hood, however, your brain creates your mind while it regulates the systems of your body. That means the regulation of your body is itself part of your mind. Science, like your brain, works by prediction and correction. Scientists use their knowledge to fashion hypotheses about how the world works. Then they observe the world, and their observations become evidence they use to test the hypotheses. If a hypothesis did not predict the evidence, then they update it as needed. We’ve all seen this process in action during the pandemic. First we heard that COVID-19 spread on surfaces, so everyone rushed to buy Purell and Clorox wipes. Later we learned that the virus is mainly airborne and the focus moved to ventilation and masks. This kind of change is a normal part of science: We adapt to what we learn. But sometimes hypotheses are so strong that they resist change. They are maintained not by evidence but by ideology. They become scientific myths. Lisa Feldman Barrett (@LFeldmanBarrett) is a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and the author of Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain. Learn more at LisaFeldmanBarrett.com. What Causes a Creative Hot Streak? A New Study Found That It Often Involves These Two Habits.

Is there a magic formula that can lead an artist to a “hot steak” of creativity? There just might be, says a new study from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. When it comes to creative careers, success can be hard to achieve and even harder to define. But what if there were a magic formula that could increase your odds of a creative breakthrough? A new study suggests that this magic formula may well exist. The secret to creativity lies in hitting “hot streaks,” or bursts of repeated successes, like Jackson Pollock’s “drip paintings” begun in the late 1940s, or Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy in the early 2000s. Published in Nature, the study explores exactly what people do before and during a hot streak. Using artificial intelligence to comb through rich datasets related to artists, film directors, and scientists, the researchers identified a pattern that is present across all three fields. The study author believes it could apply to designers, too. The secret involves experimenting with a wide range of subjects, styles, and techniques before perfecting a specific area of one’s craft—what the authors describe as a mix of exploration and exploitation. “Although exploration is considered a risk because it might not lead anywhere, it increases the likelihood of stumbling upon a great idea,” the study’s lead author, Dashun Wang, said in a statement. “By contrast, exploitation is typically viewed as a conservative strategy. If you exploit the same type of work over and over for a long period of time, it might stifle creativity. But, interestingly, exploration followed by exploitation appears to show consistent associations with the onset of hot streaks.” Wang’s findings, published in the journal Nature, sought to identify periods of intense creativity in the work of visual artists, as well as film directors and scientists. The team used image recognition algorithms to analyze data from 800,000 artworks from 2,128 artists, including Jackson Pollock, Frida Kahlo, and Vincent van Gogh. The rest of the study was based on Internet Movie Database (IMDb) data sets for 4,337 directors, and publications and citations on the Web of Science and Google Scholar for 20,040 scientists. Creative trajectories and hot-streak dynamics: three exemplary careers. Data analyzing the work of Jackson Pollock, Peter Jackson, and John Fenn. The paper identified patterns in the creators’ work over time—changes in brushstrokes, plot points or casting decisions, or research topics. It noted the diversity both in the period leading up to a hot streak, which typically lasts about five years, and at other times in the subject’s career. In all three fields, the trend tended toward a more diverse body of work in the period before a hot streak than at other points in time. Then, during the hot streak, the creators tended to continue to work in the same vein, suggesting “that individuals become substantially more focused on what they work on, reflecting an exploitation strategy during hot streak.” On Creativity and Play

Feature Artist of the week - Mark Rothko https://youtu.be/W88ly-KSHFo Excerpt: David Zhang of Guangzhou University recently led a group high into the Tibetan Tableau of Southwestern China, an area known as “the roof of the world” for its elevation 4,000 meters above sea level. There, they found a piece of limestone that had fossilized a playful composition of hand and foot impressions. The pattern was “deliberate” and “creative,” according to a paper that Zhang and fellow researchers published in the journal Science Bulletin in 2021, and the piece “highlights the central role” that artistic exploration and play has held for our species. Uranium series dating determined that this artwork could be 226,000 years old. With our hands and our feet as our first artistic tools, we’ve been leaving behind our imaginative impressions since Earth’s last ice age. Play is a key component of the arts and aesthetics in myriad ways. Art and play are like two sides of the same coin, with play being a part of artistic expression, imagination, creativity, and curiosity. Though it often gets buried in adulthood, the urge to play exists in all of us. It has been a major part of how we’ve evolved as a species. As Plato famously said, “You can discover more about a person in an hour of play than in a year of conversation.” https://nautil.us/to-supercharge-learning-look-to-play-292946/?utm_source=nautilus-newsletter&utm_medium=email&he=31b5f0083d96ee95fff1749f2477630d Sir Ken Robinson Quotes & Marco Reichert - Feature Artist of the Week

Marco Reichert: Berlin-based Marco Reichert is an emerging abstract painter who is challenging our ideas of what contemporary art is by using traditional painting techniques in conjunction with experimental “painting machines” to create multi-layered artworks. On the one hand, there is a classical pictorial methodology linked to materials and painting in the way we traditionally think of. On the other hand, there is an overtly technical-digital component through the construction of homemade machines as “robot designers” made by the artist himself. Reichert’s work is reflective of today’s society, a society that is increasingly dominated by computers and technology. We may like it or not, but technology’s influence on our everyday lives is undeniable. https://youtu.be/bf5_7-qIsCc https://bendergallery.com/artist/1290-marco-reichert SIR KEN ROBINSON. Was a British author, speaker and international advisor on education in the arts to government, non-profits, education and arts bodies. He was director of the Arts in Schools Project and Professor of Arts Education at the University of Warwick, and Professor Emeritus after leaving the university. https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity/comments Quotes “We are all born with extraordinary powers of imagination, intelligence, feeling, intuition, spirituality, and of physical and sensory awareness. ― Ken Robinson, “If you're not prepared to be wrong, you'll never come up with anything original.” ― Ken Robinson, “Human resources are like natural resources; they're often buried deep. You have to go looking for them, they're not just lying around on the surface. You have to create the circumstances where they show themselves.” ― Ken Robinson By Judy: This is precisely applicable to visual art. “For most of us the problem isn’t that we aim too high and fail - it’s just the opposite - we aim too low and succeed.” ― Ken Robinson, “Imagination is the source of every form of human achievement. And it's the one thing that I believe we are systematically jeopardizing in the way we educate our children and ourselves.” ― Sir Ken Robinson “Curiosity is the engine of achievement.” ― Ken Robinson “Creativity is as important now in education as literacy and we should treat it with the same status.” ― Sir Ken Robinson It’s about discovering your self, and you can't do this if you're trapped in a compulsion to conform. You can't be yourself in a swarm.” ― Ken Robinson, “Human communities depend upon a diversity of talent not a singular conception of ability” ― Sir Ken Robinson By Judy: That talent is precious and to discover this is not easy because there are no roadmaps. You have to search for this yourself. Anyone who shows or says “ follow me” is a disservice to you. “The arts especially address the idea of aesthetic experience. An aesthetic experience is one in which your senses are operating at their peak; when you’re present in the current moment; when you’re resonating with the excitement of this thing that you’re experiencing; when you are fully alive.” ― Ken Robinson “To be creative you actually have to do something.” ― Ken Robinson, “We stigmatize mistakes ( in art ). And running a systems where mistakes are the worst thing you can make - and the result is that we are educating students out of their creative capacities.” ― Ken Robinson “Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler did not solve an old problem, they asked a new question, and in doing so they changed the whole basis on which the old questions had been framed.” ― Ken Robinson By Judy: “So ask questions related to our class subject. There are not enough questions asked. “Young children are wonderfully confident in their own imaginations ... Most of us lose this confidence as we grow up” ― Ken Robinson, “Never underestimate the vital importance of finding early in life the work that for you is play. This turns possible underachievers into happy warriors.” ― Ken Robinson, |

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2017 IMAGES BELONG TO JUDY MAYER-GRIEVE

RSS Feed

RSS Feed