|

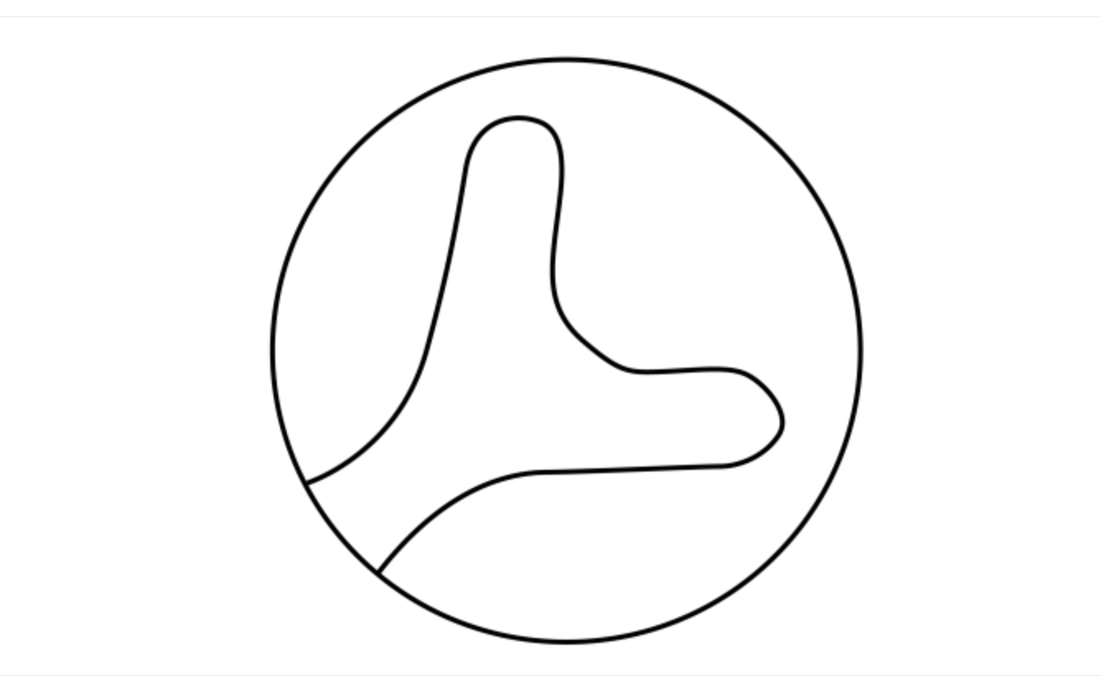

Feature Artist: Brice Marden https://youtu.be/9ebExAsHZMg That’s not how the Brain Works. Lisa Feldman Barrett (@LFeldmanBarrett) is a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and the author of Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain. Learn more at LisaFeldmanBarrett.com. Forget scientific myths to better understand your brain and yourself. So why does the myth of a compartmentalized brain persist? One reason is that brain-scanning studies are expensive. As a compromise, typical studies include only enough scanning to show the strongest, most robust brain activity. These underpowered studies produce pretty pictures that appear to show little islands of activity in a calm-looking brain. But they miss plenty of other, less robust activity that may still be psychologically and biologically meaningful. In contrast, when studies are run with enough power, they show activity in the majority of the brain, Pretty much everything that your brain creates, from sights and sounds to memories and emotions, involves your whole brain. Every neuron communicates with thousands of others at the same time. In such a complex system, very little that you do or experience can be traced to a simple sum of parts. Brains don’t work by stimulus and response. All your neurons are firing at various rates all the time. What are they doing? Busily making predictions. In every moment, your brain uses all its available information (your memory, your situation, the state of your body) to take guesses about what will happen in the next moment. If a guess turns out to be correct, your brain has a head start: It’s already launching your body’s next actions and creating what you see, hear, and feel. If a guess is wrong, the brain can correct itself and hopefully learn to predict better next time. Or sometimes it doesn’t bother correcting the guess, and you might see or hear things that aren’t present or do something that you didn’t consciously intend. All of this prediction and correction happens in the blink of an eye, outside your awareness. If a predicting brain sounds like science fiction, here’s a quick demonstration. What is this picture? If you see only some curvy lines, then your brain is trying to make a good prediction and failing. It can’t match this picture to something similar in your past. (Scientists call this state “experiential blindness.”) Then come back and look at the picture again. Suddenly, your brain can make meaning of the picture. The description gave your brain new information, which conjured up similar experiences in your past, and your brain used those experiences to launch better predictions for what you should see. Your brain has transformed ambiguous, curvy lines into a meaningful perception. (You will probably never see this picture as meaningless again.)

You’re not a simple stimulus-response organism. The experiences you have today influence the actions that your brain automatically launches tomorrow. The myth is that there’s a clear dividing line between diseases of the body, such as cardiovascular disease, and diseases of the mind, such as depression. The idea that body and mind are separate was popularized by the philosopher René Descartes in the 17th century (known as Cartesian dualism) and it’s still around today, including in the practice of medicine. Neuroscientists have found, however, that the same brain networks responsible for controlling your body also are involved in creating your mind. A great example is the anterior cingulate cortex, mentioned earlier. Its neurons not only participate in all the psychological functions, but also they regulate your organs, hormones, and immune system to keep you alive and well. Every mental experience has physical causes, and physical changes in your body often have mental consequences, thanks to your predicting brain. In every moment, your brain makes meaning of the whirlwind of activity inside your body, just as it does with sense data from the outside world. When thinking about the relationship between mind and body, it’s tempting to indulge in the myth that the mind is solely in the brain and the body is separate. Under the hood, however, your brain creates your mind while it regulates the systems of your body. That means the regulation of your body is itself part of your mind. Science, like your brain, works by prediction and correction. Scientists use their knowledge to fashion hypotheses about how the world works. Then they observe the world, and their observations become evidence they use to test the hypotheses. If a hypothesis did not predict the evidence, then they update it as needed. We’ve all seen this process in action during the pandemic. First we heard that COVID-19 spread on surfaces, so everyone rushed to buy Purell and Clorox wipes. Later we learned that the virus is mainly airborne and the focus moved to ventilation and masks. This kind of change is a normal part of science: We adapt to what we learn. But sometimes hypotheses are so strong that they resist change. They are maintained not by evidence but by ideology. They become scientific myths. Lisa Feldman Barrett (@LFeldmanBarrett) is a professor of psychology at Northeastern University and the author of Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain. Learn more at LisaFeldmanBarrett.com.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2017 IMAGES BELONG TO JUDY MAYER-GRIEVE

RSS Feed

RSS Feed